2 changed files with 108 additions and 0 deletions

Split View

Diff Options

-

+108 -0content/2021/07/CODEpendence-github.html

-

BINcontent/media/images/codependence-comp-author.png

+ 108

- 0

content/2021/07/CODEpendence-github.html

View File

| @@ -0,0 +1,108 @@ | |||

| --- | |||

| title: CODEpendence | |||

| description: > | |||

| How to surreptitiouslyinject code via submodules that use GitHub repos | |||

| created: !!timestamp '2021-07-07' | |||

| time: 11:16 AM | |||

| tags: | |||

| - security | |||

| - GitHub | |||

| - git | |||

| --- | |||

| TL;dr: If you use submodules that point to a GitHub repo, make sure | |||

| that the commit id matches an offical branch or tag, especially if | |||

| upgraded via a PR or submitted patch. | |||

| This issue was disclosed to GitHub via the HackerOne Bug Bounty | |||

| program and resolved by them in a timely manner. The | |||

| [writeup](https://www.funkthat.com/~jmg/github.submodules.hash.txt) is | |||

| available and is the same one that was provided to GitHub. It contains | |||

| the complete steps in more detail than this blog post does. | |||

| Discovery | |||

| --------- | |||

| Earlier this year, I was dealing with a git repo that used submodules. | |||

| I've never been a fan of them due to the extra work involved in using | |||

| them. But then a thought hit me, last year, when GitHub took down | |||

| youtube-dl, someone was a bit sneaky and inserted a [copy of it into | |||

| GitHub's DMCA repo](https://www.reddit.com/r/programming/comments/jhlhok/someone_replaced_the_github_dmca_repo_with/). | |||

| They were able to do this because there is a feature/bug in GitHub's | |||

| backend, that all the commits to a forked repo are accessible in the | |||

| parent repo, it's just that the branches and tags are maintained | |||

| separately.<label for="sn-reason" class="margin-toggle sidenote-number"> | |||

| </label><input type="checkbox" id="sn-reason" class="margin-toggle"/> | |||

| <span class="sidenote">This makes sense to reduce storing duplicate data | |||

| if a repo is large or has many forks.</span> | |||

| Verification | |||

| ------------ | |||

| The next question, would combining these into an attack even work? | |||

| What would things look like? I created a few accounts to test them, | |||

| creating a project to represent a code dependancy, | |||

| [depproj](https://github.com/upstream123/depproj), that would be | |||

| imported into another project by another user, | |||

| [proj](https://github.com/comproj/proj). Then once those were created, | |||

| have a malicious user create a fork of both the | |||

| [deprpoj](https://github.com/maliciousrepo/depproj) and the | |||

| [proj](https://github.com/maliciousrepo/proj). | |||

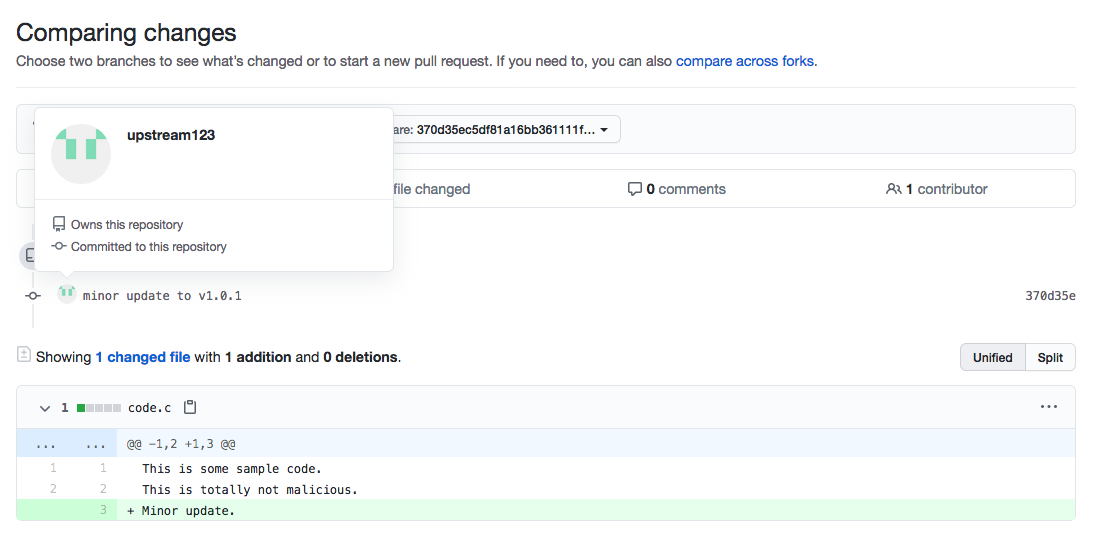

| Once the malicious forks were created, clone them locally. With the | |||

| clones, malicious [code can be | |||

| inserted](https://github.com/maliciousrepo/depproj/commit/91781e4b9e1b1c944e19db740db12304755666b5) | |||

| into the depproj repo. If you look at the repo, the previous commit | |||

| was done as the maliciousrepo user, but while I was working on this, | |||

| I remembered that w/ git, you can set the commit author to be anything | |||

| (signing helps prevent that), so this commit appears to be done by the | |||

| correct upstream123 user. | |||

| Once the malicious code has been inserted, the malicious user can now | |||

| update the submodule of the project to the commit id of the malicious | |||

| code. This is done simply by doing: | |||

| ``` | |||

| cd depproj | |||

| git fetch origin <commitid> | |||

| git checkout <commitid> | |||

| ``` | |||

| Even though the depproj still points to the upstream123 repo, because | |||

| fork commits appear IN the depproj repo, the above works w/o any other | |||

| changes. This is also what makes it dangerous, because the repo is not | |||

| changed, it can be disguised as a simple version update. | |||

| A [PR](https://github.com/comproj/proj/pull/3) is then submitted to the | |||

| project being attacked. I did not control the author of commits as | |||

| well as I should have, but it still is effective. If you click into | |||

| the proposed change, and then click on code.c, the file changed, it'll | |||

| bring you to the [change compare | |||

| view](https://github.com/upstream123/depproj/compare/91781e4b9e1b1c944e19db740db12304755666b5...370d35ec5df81a16bb361111faeb665ea90de026#diff-e43700a08429a0231daba9a49ff36a118566849856da2811ae074417ebb552d0). | |||

| For this demo, it was a small change, but if the project is large, it's | |||

| would be easy to bury a minor flaw in lots of changes. The other thing | |||

| to note about this page is that the author displayed is NOT the author | |||

| of the change, but it appears that it is a legitimate change by the | |||

| author of the repo. []({{ media_url('images/codependence-comp-author.png') }}) | |||

| Conclusion | |||

| ---------- | |||

| This is an interesting attack in that it leverages two features in a | |||

| way that has surprising results. It demonstrates that software | |||

| dependancies need to be reviewed, and vetted, and that if you're using | |||

| GitHub, that just because a PR says it's updating a submodule to the | |||

| new version, it doesn't mean that it is safe to simply merge in the | |||

| change. | |||

| Timeline | |||

| -------- | |||

| 2021-03-31 -- Reported to GitHub via HackerOne.<br> | |||

| 2021-03-31 -- More info requested and provided.<br> | |||

| 2021-04-01 -- Ack'd issue and started work on fix.<br> | |||

| 2021-05-04 -- GitHub determined it was low risk, but did add warning when viewing commit.<br> | |||

| 2021-05-05 -- Asked GitHub for disclosure timeline.<br> | |||

| 2021-06-04 -- Pinged GitHub again.<br> | |||

| 2021-07-07 -- Published blog post.<br> | |||